As the criminal migrant crisis continues at the U.S. southern border, authorities have reported increasing encounters with unaccompanied children (UC).

By law, when a solo minor is apprehended crossing the border, they fall under the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), which then places the child with a sponsor family somewhere in the United States. However, it's what happens next that has many concerned with the child's well-being.

Family Services of North Alabama executive director Sherrie Hiett said after a child is placed in a sponsor home, typically with a relative, little to nothing is done to keep track of their location or quality of care, which increases their risk of being mistreated or trafficked.

Family Services is located in Marshall County, which has one of the highest populations of UCs, second only to Jefferson County.

"Whenever a child is placed in Marshall County or in any county, only 6.7% of those children have an actual home study done before they're placed. So that in itself is a problem," Hiett said. "They're not on DHR's radar. They're not on law enforcement's radar. They're placed in these homes, they get about four weeks of case management. After the four weeks of case management, they're kind of on their own with these sponsor families."

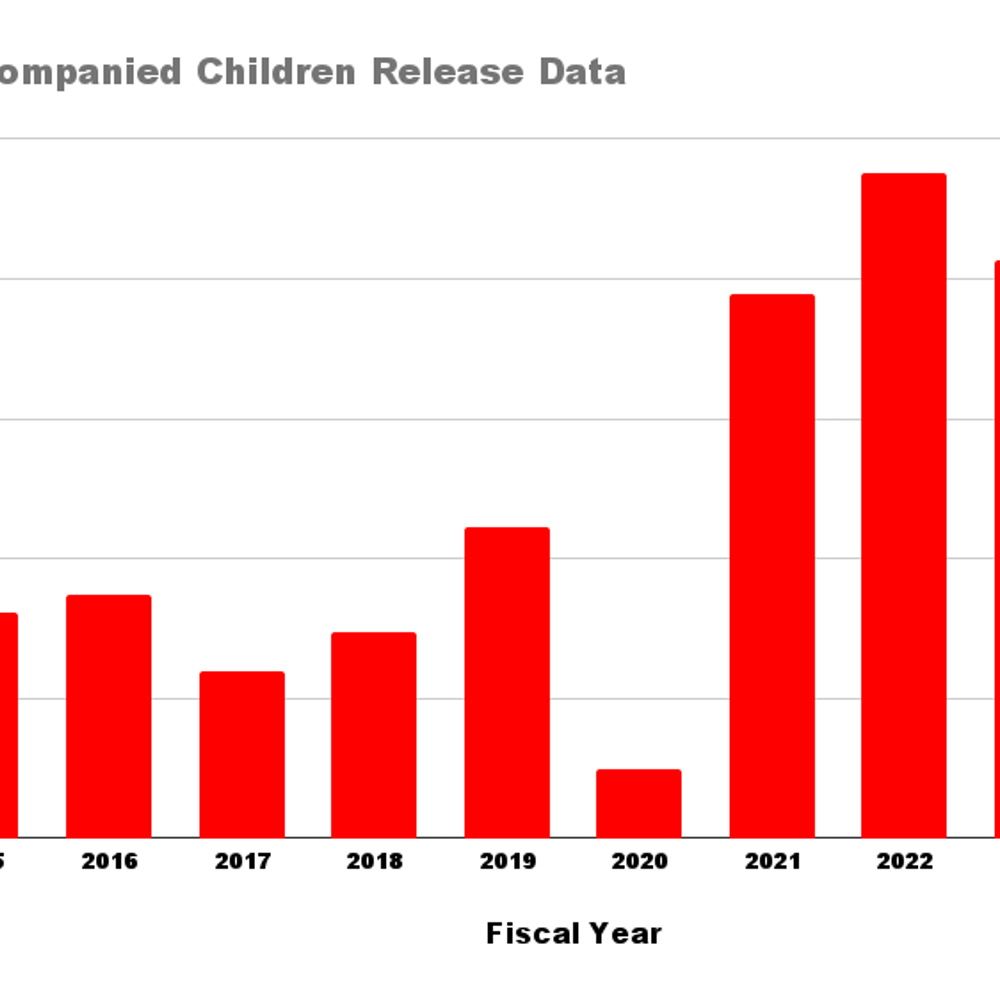

The ORR has placed over 700,000 unaccompanied minors in sponsor homes since it began its Unaccompanied Children Program in 2003 after the Homeland Security Act of 2002 shifted the responsibility from the former Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Since 2014, the ORR reportedly placed 11,585 migrant children in sponsor homes in Alabama, where the per-year number has seen a significant increase under the Biden administration — nearly 192% over the last three years, Hiett said.

The annual average of UC placements from October 2014 to September 2020 was 728 versus 1,804 from fiscal year 2021 to date, which includes 827 between October 2023 and January 2024 — more than the total reported for fiscal years 2015, 2017, 2018 and 2020.

According to ORR data, in fiscal year 2023 (October 2022-September 2023), approximately 76% of all unaccompanied migrant children referred were over 14 years of age, and 61% were boys. Approximately 42% were from Guatemala, 28% from Honduras, 9% from El Salvador, 8% from Mexico and 13% from other unspecified countries.

Hiett said that, unlike traditional foster families, these sponsor homes receive no federal money to house the unaccompanied child immigrants. And though many of the families claim to be related, often that is not the case, she said.

"You have to kind of wonder, if they're not family, then why are they taking them in, unless they're just that good of people," she said.

Hiett said it's common for these children, after their case management time has expired, to be unenrolled from school and virtually disappear.

"They might come in and say, 'Hey, we're going to unenroll them. They're going back to Guatemala. Or they're going to go to this [other] school or whatever.' But there's no follow-up, and a lot of kids go missing. That's why they're called 'ghost kids.'"

Hiett said that it's not always the case that these missing kids are being trafficked, but it remains a real concern. As a rape crisis center, Family Services already sees trafficking victims, she said.

"That's not always happening, but it's not not always happening either. The gap there is case management," she explained. "...The number of trafficking victims that we see most is familial trafficking, meaning kids are being rented out by their parents for a hit of drugs or a place to stay or whatever that looks like."

She said drug addiction plays heavily into the problem, as Alabama's fourth congressional district has one of the highest opioid prescription rates in the country. Labor trafficking is also a major concern, Hiett said, given the area's high concentration of Hispanic and Latino immigrants.

"There's kind of this perfect storm for our area," she outlined.

Marshall County's many chicken processing plants and other industries have made the area a magnet for immigrants, legal or otherwise. In particular, Wayne Farms in the heart of Albertville played a major role in the mass migration of Hispanics in the 1990s, forever changing the small town.

RELATED: Albertville: How lax immigration policy drastically changed the character of an Alabama town

More recently, a 2023 report by The New York Times told of how Farm Fresh Foods, a meat packing plant in Guntersville, often encountered migrant minors in the hiring process. One of their human resource managers, Charlene Irizarry, told the Times that the too-young applicants would sometimes wear heavy makeup or facemasks to "hide their youth."

Hiett is currently applying for a grant to help provide more services and outreach to trafficked victims and to fund two full-time investigators in Marshall and DeKalb Counties so local law enforcement can keep track of the sponsored kids.

Marshall County Sheriff Phil Sims said he was unaware of how prevalent the issue was in the state, let alone his county, until an incident at a local school regarding a student's alleged uncle raised some "red flags." Sims discovered the uncle had seven children in the system he was responsible for, all of whom were supposedly his nephews.

"This guy had seven nephews in school, and we're like, 'Now that don't sound right,'" Sims said. "I think, in that case, everything's legit there… He's not really their uncle; he's just a sponsor."

Sims said he hasn't seen any confirmed cases of child trafficking in his county, and he wants to keep it that way.

"I'm not saying that is what is going on. What I'm saying is, we have no way of tracking if these kids are being cared for," he stated. "In foster care, there is a mechanism in place through DHR. In this instance with undocumented children, there's not a mechanism in place. The opportunity for human trafficking is there."

Sims referred to a recent sting operation where five suspects were arrested for attempting to meet an underaged child.

"It's a problem everywhere. We focused on Marshall County because that's our jurisdiction. But the majority of those cases come from out of county and one from out of state," Sims said. "That's typical when you start doing these sting operations… There were a lot more conversations and a lot more hits, just the people didn't show up."

Sims said he hopes to draw attention to this issue and eventually devote more manpower to tracking the children's well-being once they're placed with sponsors.

"How do we know where these kids are at, how do we know when they come into town, how do we know they are living in our communities? We don't know any of that yet. It's going to take some work to do it. The problem is we don't have the manpower to dedicate just one person to it full-time. But we're going to have to do something," he said.

Covenant Rescue Group, founded by U.S. Navy Seal Jared Hudson, helped set up the sting in Marshall County as part of a training exercise. He said regardless of what the current rate of child trafficking or assault is in Alabama, the risk is always highest among unaccompanied minors and those in poverty.

"Those are your children that are at the highest risk for being stolen, used, sold, neglected whether it's labor trafficking or sex trafficking," he told 1819 News. "They're either already being used or exploited, or they're at an extremely high risk of being exploited."

A major part of the problem, Hudson said, is the federal government's reluctance to address the issue, an "unwillingness to do the right thing at an administration level."

Hiett said she, too, was tired of the political infighting surrounding the issue and that she and others on the "front lines" were being "overwhelmed."

"This is not a red or blue issue. This is a child issue," she said. "We're not going to get involved in the political aspect of it because we're on the frontlines dealing with the effects of these parties fighting."

In December 2023, U.S. Sens. Tommy Tuberville (R-Auburn) and Katie Britt (R-Montgomery) signed a letter along with several other lawmakers demanding ORR enact stricter sponsor vetting processes.

"ORR does not even consider a sponsor's criminal record, current illegal drug use, history of abuse or neglect, or other child welfare concerns' necessarily disqualifying to potential sponsorship.'… In effect, ORR accepts a sponsor's representations almost entirely on face value," the letter stated.

In a press release issued on March 1, ORR said, "Sponsors are required to undergo background checks and complete a sponsor assessment process that identifies risk factors and other potential safety concerns." However, not every sponsor receives a home study.

1819 News contacted ORR to see if any changes had been made as a result of the senators' letter. We have yet to receive a response.

To connect with the story's author or comment, email daniel.taylor@1819news.com or find him on Twitter and Facebook.

Don't miss out! Subscribe to our newsletter and get our top stories every weekday morning.