Historical events from 163 years ago in Alabama were featured on Sunday's CBS's "60 Minutes."

How is it that Alabama events of the Civil War era are still news on major, well-watched American media?

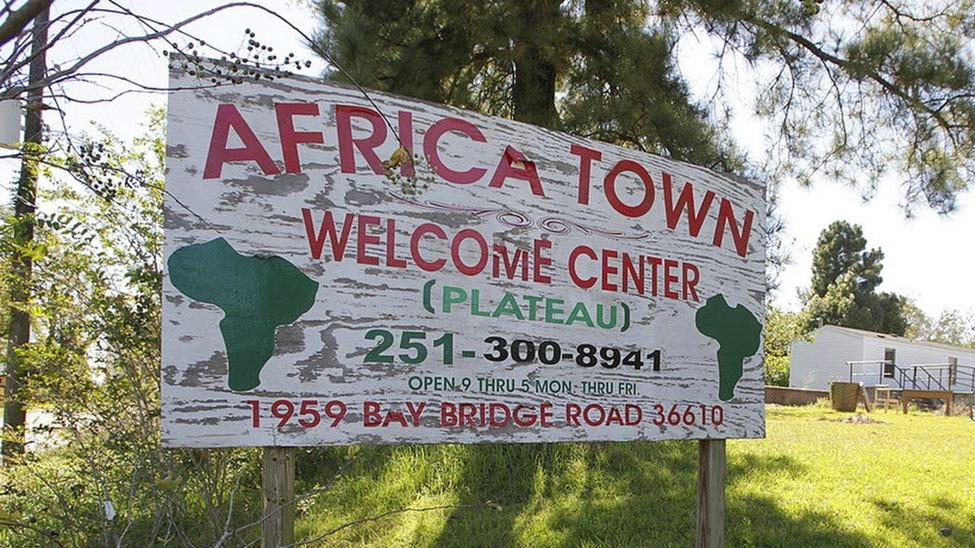

The two-fold reason is that descendants of the last slave ship are still living in the small, black community of Africatown in Mobile, taking steps to memorialize the sufferings of their enslaved ancestors and to make Africatown a thriving community. The descendants of the financier of the slave ship are still in Mobile, enjoying multi-generations of business success and are now taking steps to reach out and assist the Africatown descendants.

The interaction of those two descendant groups began only on July 23 of this year when descendants of financier Timothy Meaher met for the first time with descendants of slaves he paid for and brought from Africa on the illegal ship Clotilda. Those two groups also shared a table on "60 Minutes."

Descendants of Timothy Meaher – who had hired Capt. William Foster to smuggle 110 captive Africans to Mobile on his ship, Clotilda - were represented on the show and in the July 2023 first-time meeting by two Meahers: Meg, an accountant, and her sister Helen, an attorney. They are the great-great-grandchildren of Timothy Meaher.

This "60 Minutes" was moderated by Anderson Cooper of CBS News.

Over the last year, these two Meahers have explored what they might do to make amends for things they never did that their 1860s ancestor did. Things they have no legal obligation to repair.

Slavery was still legal in the southern United States in 1860 when Timothy Meaher hired Captain Foster and his ship. Importation of slaves into America had been outlawed in 1808, 52 years before.

Timothy Meaher dispatched the ship to Dahomey, West Africa, where Foster purchased 110 captives using $9,000 in gold from Meaher.

The enslaved Africans were locked naked in the cargo hold of the Clotilda. The ship was designed so the human cargo was crammed into shelves. Men were allowed a foot and a half of space between shelves, women a foot and four inches and children one foot.

Forty-five days later, the 110 men, women and children arrived in Mobile and were handed over to Meaher and a brother. Foster then had the Clotilda moved upstream to an isolated area of the Mobile River, burned and sunk. The Clotilda is the last known ship to bring enslaved Africans to America.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation and the Union victory in the Civil War, the Clotilda survivors were freed after five years of slavery.

In 1868, 30 of the freed Africans from the Clotilda founded Africatown. It's now the only surviving community in America founded by Africans. Some of their descendants still live there.

Around 800 people live in Africatown, down from a high of 12,000 in the 1960s. A federal highway was built through the middle of Africatown, and the small clusters of remaining homes are surrounded by factories and plants, which can be heard in operation 24 hours a day.

Timothy Meaher's descendants still own an estimated 14% of the land in historic Africatown, according to tax records. Their name is on nearby street signs and property markers, a constant reminder of their slave ownership.

The wreckage of the Clotilda was discovered in 2018 in a nearby part of the Mobile River by journalist Ben Raines. Maritime archaeologists confirmed the ship was the Clotilda in 2020. Raines wrote a book about the Clotilda in 2023.

Since the Clotilda's discovery, outside interest in restoring Africatown has increased. Over $10 million in city, state, federal and private funds have gone into revitalizing Africatown. Citizen groups compete for the funds and the leadership role in representing Africatown and its ancestors.

In the July first-time meeting with the Meahers, the Clotilda Descendants Association was represented by Pat Frazier, the great-great-granddaughter of slave Lottie Dennison; descendant Joycelyn Davis; and organization president Jeremy Ellis.

Descendants of enslaved Africans brought to Alabama on the Clotilda and descendants of Timothy Meaher, who arranged the ship, sat down to talk (Moderated by Anderson Cooper).

Helen Meaher grew up just a few miles from Africatown, but she had never been there until 2022, when she started volunteering at a food bank. In 2021, she and Meg sold a plot of land in Africatown to the City of Mobile for $50,000, a fraction of its appraised value. It will be home to community development organizations and a new food bank.

She hopes that in 10 years, Africatown will be a thriving community.

Frazier doesn't hold the Meaher sisters responsible for what their ancestor did.

"However, I want them to recognize how that behavior benefited them and worked to the disadvantage of us," she said. "Just like they've had multiple generations of wealth, the original slaves and their descendants haven't."

The Clotilda descendants at the meeting stressed that they weren't asking for reparations, but rather reconciliation.

"I have a daughter and I believe that she should have the same level of education that the Meaher family experienced," Ellis said. "We believe that the same level of education should be provided to all descendants."

They also believe there are parcels of land in historic Africatown that they should have ownership in.

"We're still keeping an open mind, and working on figuring out next steps," Helen Meaher said. "And I'm not shutting a door on anything."

The July meeting between the two descendant groups lasted two hours. Though no financial commitments were made, the Meahers have begun removing their property markers and say they're consulting with financial advisers and local groups to see what their next steps might be.

"They've come to the table, trying to do the right thing," Jeremy Ellis said.

In the July meeting and on "60 Minutes," the following phrases were often heard:

"Reconciliation."

"Healing process."

"Land trust."

"Scholarships."

"Thriving community."

A word you did not hear much, other than denying that it was being sought, was: "Reparations."

See the full segment here.

Jim Zeigler is a former Alabama Public Service Commissioner and State Auditor. You can reach him for comments at ZeiglerElderCare@yahoo.com

Don't miss out! Subscribe to our newsletter and get our top stories every weekday morning.