“Accidents” of history are sometimes the Providence of God.

In 1620 the Pilgrims sailed for America, intending to plant a colony in northern Virginia. But a storm blew them off course, and they found themselves off the coast of Massachusetts. Realizing God had steered them northward so they would not be under the authority of the Virginia Colony, they were now free to draft their own articles of government.

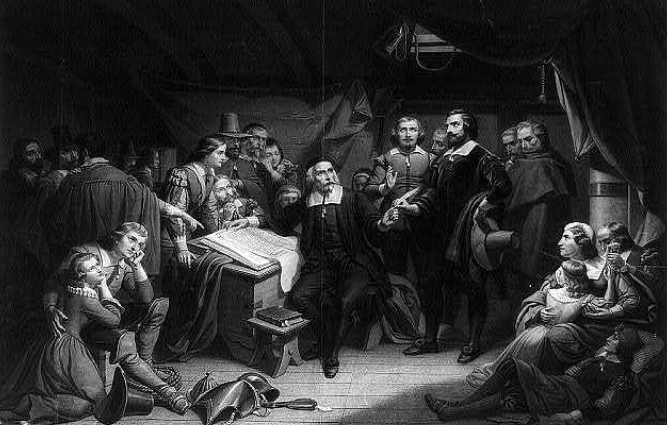

So before they stepped ashore, they gathered aboard the Mayflower and drafted the Mayflower Compact, described by John Quincy Adams in 1802 as “the only instance in human history of that positive social compact.” It reads:

“IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience.

IN WITNESS whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape-Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini; 1620.”

Simple words. But they convey the basic principles of law and government that influenced future generations to draft colonial charters and, later, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

The Compact recognized, first, that God is the Source of all governmental authority. The Pilgrims spoke of the “Grace of God,” the Name of God, the Presence of God, and the Glory of God, declaring that their purpose was the “advancement of the Christian faith.” They knew that God gives governmental authority to the people, and people in turn delegate that power to rulers.

They were not opposed to kings – that would come later. They acknowledged King James I as the God-ordained king of Great Britain and [North] Ireland, and they even recognized his disputed claim over portions of France that arose after Henry V defeated the French at Agincourt in 1415.

But they had come to these distant shores as English colonists with leave to establish their own form of government. So they combined themselves together into a “civil Body Politick” through which they would achieve their “better Ordering and Preservation” (creating an orderly system under which they could function) for the “Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid” (the Glory of God and the Advancement of the Christian faith).

To achieve these purposes, they acknowledged that God had given them authority to establish civil government by social contract. But where did they learn about social contract?

As students of the Bible, they knew that this authority arose with the covenant God established with Noah after the Flood (Genesis 9:1-17) and with the governing authority God gave to parents over their children (Exodus 20:12), authority which parents delegate in part to civil government. John Locke, in his “First and Second Treatises on Civil Government,” cited these Scriptures as the source of all governmental authority.

But the Pilgrims didn’t learn about social contract from John Locke. They sailed to Plymouth in 1620, and Locke didn’t write until 1689. More likely, they learned theories of social contract from Dutch theorists such as Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) during their sojourn in Leiden, Holland (1608 – 1620). Few Americans appreciate the extent to which we are indebted to the Dutch for our views of a constitutional republic.

The Pilgrims acknowledged the authority of the colonial government created by the Mayflower Compact to “enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony.” Just as “We the People” delegated certain powers to the federal government through the Constitution, so “They the Pilgrims” delegated certain powers to the government of Plymouth Colony through the Mayflower Contract.

But that governmental authority was limited. To be valid, laws must be:

(1) “Just.” Laws must be fair and in accord with the Higher Law of God. Our Declaration of Independence acknowledges “the laws of nature and of nature’s God.”

(2) “Equal.” Laws must apply equally to everyone in the colony. One hundred fifty-six years later, the Declaration of Independence would declare that all men are “created equal,” and in 1868 the 14th Amendment would guarantee the “equal protection of the law.”

(3) “Meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony.” To be just and equal, laws must benefit all, not just a select few.

To this colonial government, and to these laws, the Pilgrims promised “all due Submission and Obedience.” Not absolute obedience; rather, “due” obedience. So long as rulers stayed within their God-appointed limits, and so long as the laws they enacted were just, equal, and for the general good, they would obey. But if the government were to become tyrannical, they reserved the right to disobey, for rebellion against tyrants is obedience to God. A century and a half later, their descendants would remember these words as they declared independence from a king who had become a tyrant.

The Pilgrims weren’t perfect. If they ever thought so, their own Calvinistic theology with its emphasis on total depravity would remind them of that.

But they dared to do great things for God, risking their lives on a dangerous passage to an unknown wilderness. They established a colony that eventually flourished, governed it peacefully, and sealed a peace treaty with Chief Massasoit and the Wampanoag that endured for over half a century. And they declared, with Governor Bradford in his History of Plymouth Plantation, “Let the glorious Name of Jehovah have all the praise!”

Colonel Eidsmoe serves as Chairman of the Board for the Plymouth Rock Foundation (plymrock.org), as Professor of Constitutional Law for the Oak Brook College of Law & Government Policy (www.obcl.edu), and as Senior Counsel for the Foundation for Moral Law (www.morallaw.org). He may be contacted for speaking engagements at (334) 324-1812. Those with constitutional issues may contact the Foundation at (334) 262-1245.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of 1819 News. To comment, please send an email with your name and contact information to Commentary@1819news.com.

Don’t miss out! Subscribe to our newsletter and get our top stories every weekday morning.