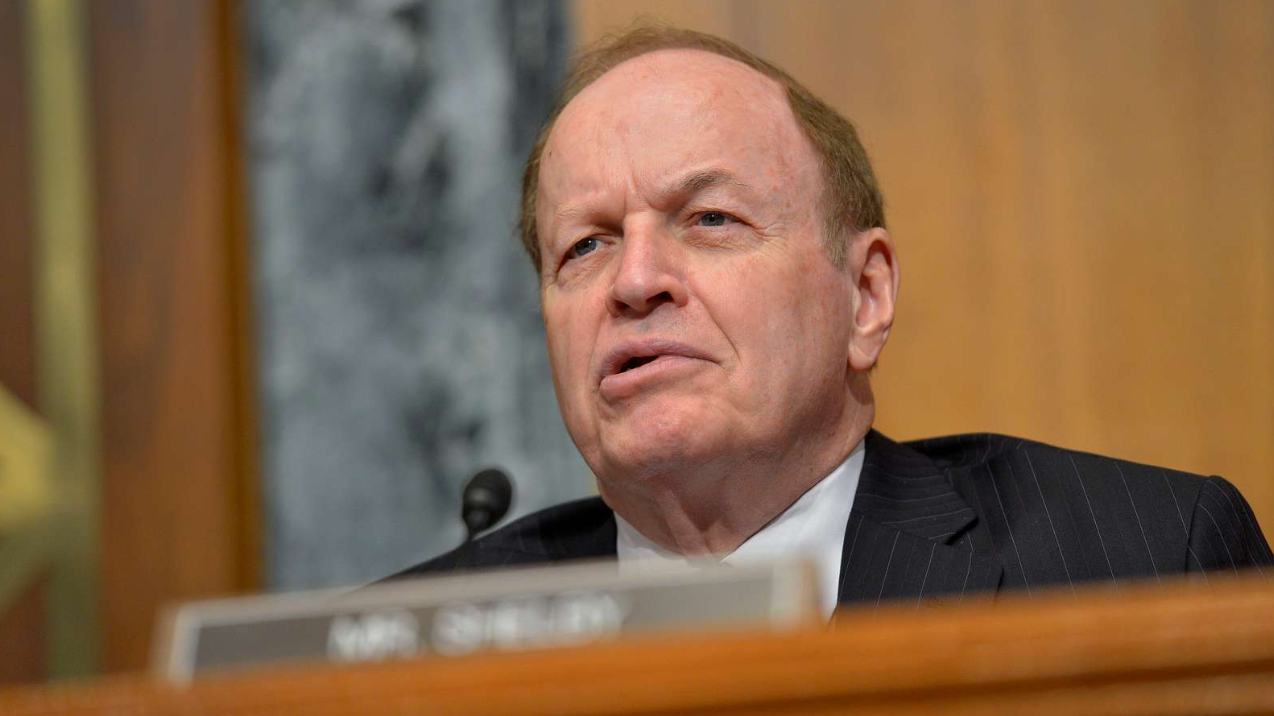

Newly retired U.S. Sen. Richard Shelby achieved national prominence for bringing earmarked funds to Alabama. “In the game of earmarks, Shelby has no peers,” “Roll Call” once said of the senator. Empowered by his position as the ranking Republican on the Senate Appropriations Committee, Shelby led all members of Congress in earmarked funds the last two years, finishing his Senate service with $666 million in December’s appropriations bill.

Many would argue that earmarks undermine fiscal conservatism, waste tax dollars, and bankrupt our nation. But I believe that such arguments—particularly the one about earmarks preventing fiscal conservatism—must rely on hypocrisy.

For starters, December’s appropriations bill included $15 billion in earmarks. This was less than one percent of the $1.7 trillion appropriated, near the long-term average. Thus, it seems apparent that earmarks have largely not produced America’s $31 trillion national debt and bankrupted our nation.

A prominent earmarker such as Shelby can support fiscal conservatism without hypocrisy. Earmarking is a classic prisoner’s dilemma game like the one states use in targeting incentives to attract businesses. Big spenders typically engage in extensive logrolling, voting for each other’s earmarks. Sen. Shelby could not refrain other members of Congress from pursuing earmarks even if he himself stopped doing so. A legislator could reasonably say, “as long as this is allowed, I will pursue a share.”

Whether earmarking allocates tax dollars poorly is unclear. Politics, banking, and charity all involve people asking others for financing. We must carefully examine the details to detect differences. For this, we turn to economist Milton Friedman.

Friedman suggests that there are two relevant considerations in spending. The first is whether someone spends their own money or someone else’s, while the second is whether a person spends for themselves or someone else. In government, politicians spend taxpayers’ money on others. Friedman implies that this the worst combination, for decision-makers will not fear wasting others’ money and will be unconcerned about the quality of what they purchase.

But is earmarked spending worse than regular appropriation spending? With earmarks, one representative decides a project is worthy and champions it. Alternatives to earmarking include congressional committees allocating funds or bureaucrats spending an appropriated budget. Bureaucratic committees naturally have predictable biases. One might ask whether bureaucrats in the Department of Health and Human Services would have spent the $76 million Shelby earmarked for the University of Alabama at Birmingham biomedical research facility better. By exercising good judgment, Shelby and his staff could easily find deserving projects bureaucrats would not fund.

Members of Congress also rely on one another to ensure the respectability of earmarks, and a representative bringing enormous criticism on Congress will likely find her future earmarks limited. Sen. Rand Paul’s (R-KY) annual Festivus, for example, highlights Washington’s most outrageous spending. One of this year’s highlights was a $119,000 National Science Foundation grant to study if Marvel’s Thanos could snap his fingers while wearing the Infinity Gauntlet. Such potential for blowback limits congressmen from making totally ridiculous earmarks.

But isn’t most government spending wasteful? Perhaps, but as the late economist William Niskanen observed after 25 years in Washington, he never once saw a budget line labeled, “Waste, Fraud, and Abuse.” Almost every government project, even those Sen. Paul ridicules, produce some benefit. Benefits are ultimately subjective, and some people will likely view the most wasteful programs worthwhile. The benefits of wasteful projects do not exceed their costs.

Ending earmarks will not bring America fiscal salvation, since Congress “banned” earmarks between 2010 and 2020 (although this characterization was overstated). While spending slowed in the first years of the 2010s, I attribute this to Tea Party Republicans’ unwillingness to spend as President Obama desired more than the banning of earmarks.

Sen. Shelby’s retirement will reduce the flow of federal dollars earmarked to Alabama. Any increase in the moral authority of Alabama’s delegation to cut spending with Shelby’s retirement is unlikely to make up for our diminished earmarks.

Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.

Don't miss out! Subscribe to our newsletter and get our top stories every weekday morning