The largest political corruption trial in history ended 150 years ago with the conviction of one William M. "Boss" Tweed, whose vice was so vast and comprehensive that no one is quite sure of how much money he actually stole.

Estimates range from $50 million to $200 million, which, when converted from 1873 dollars, amounts to roughly $1.5 to $3.7 billion today.

Tweed's conviction makes other cases of political corruption seem like mere misdemeanors or foot faults, but his ability to marshal votes is still the envy of political leaders. In fact, he was the first community organizer who realized that there was strength in numbers and votes in political patronage.

The son of tough Scotsmen, Tweed emerged as a leader who could motivate people and capture their imagination by providing for their creature comforts. A leader for a volunteer fire department, he eventually became a New York City alderman, continuing his political climb by serving in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Tweed was merely one of a large number of legislators in Washington, so he quickly tired of his lack of influence and realized that the Big Apple was the place to be, heading home after only one term in Congress. Thus began his rise as the unofficial mayor of New York City and shadow governor.

Early in life, Tweed showed an interest in accounting and learned very quickly how numbers and dollar signs worked together. He realized, too, that with the jobs created by the industrial revolution, there was strength and votes in the numbers of workers. By pandering to the Irish immigrants flooding New York, he made friends who would blindly follow him into the voting booths.

Tweed's sharp elbows landed him in a leadership role in the political machine of all machines: Tammany Hall. Originally organized as a social club for well-heeled New Yorkers, it developed into a well-oiled party machine controlling votes and public patronage jobs, operating as the de facto New York City Democratic Party.

Although he would never be elected to office again, Tweed would create an organization that exercised almost absolute control over politics in New York State. Although a problem solver with great political instincts, Tweed became ostentatiously corrupt rather than use these talents for good, eventually inviting enemies.

His first real start in local politics came during the Civil War with the draft riots in New York City. Lincoln imposed a draft providing an "exemption" for people who provided a substitute, but the idea of paying for a substitute only benefited the wealthy, excluding the more numerous working class who rioted at being pressed into service.

Tweed realized that catering to the working class was good for them, but even better for himself. So, he established true exemptions for police and fireman while also utilizing a slush fund to help working class men pay for substitutes. This pressure release curbed further riots and fostered peaceful streets.

This achievement was remarkable for ending the riots while creating a block of voters who could be counted on to vote at Tweed's direction. Using this block, he prevailed upon officials in Albany to change the law to allow New York City to have more local control so that contracts for city services would escape the scrutiny of state lawmakers.

This was Tweed's most selfish act as he realized that by securing home rule and using his position at Tammany, he could direct contracts and receive a commission for his work. Initially, this "commission" didn't benefit him exclusively but was partially used to provide social services to the working classes, building churches, schools, and hospitals. In doing so, he added to his loyal following.

Tweed became a sort of Robin Hood, taking money from city vendors and helping the poor. He would argue that this was "honest" graft, which justified corruption because others benefited. While others did benefit and the services provided were real and significant, Tweed was not a distant beneficiary. From almost every city contract, Tweed profited. He did share the wealth, but it was a fraction of the graft he kept for himself.

As dealing with Tweed became part of the cost of doing business in New York, he emerged as the father of all patronage, doling out jobs and favors to his constituents.

Tweed was all three branches of government rolled into one person; nothing escaped his influences. Judges and courts were in his employ, legislators owed him their livelihood, and mayors and governors depended on his block votes for election.

But, as his power grew and he flaunted his wealth, he developed enemies, alienating friends who became focused on ending his influence. Two isolated incidents started his downfall. First, he would tangle with the governor over something as insignificant as the Orange Day parade. Much like the draft riots, the parade by Scotch-Irish Protestants enflamed the Irish Catholics, and Tweed lost control of the streets of New York when more than 125 people died.

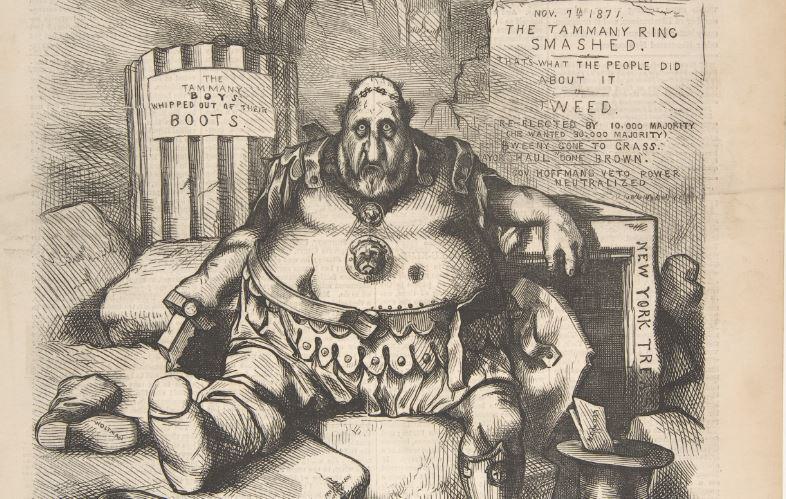

Around the same time, a former friend who had been rejected for political patronage, secretly smuggled Tweed's accounting records detailing his corruption. This road map was turned over to a reporter for a fledging newspaper, “The New York Times,” and it began publishing the breadth of Tweed's larceny. While the writing was incriminating enough, Tweed feared the political cartoons more than anything as even illiterate New Yorkers could understand the magnitude of his graft, kickbacks, and malfeasance.

Tweed was tried, convicted, and sentenced to jail, but his influence was still great, and he was allowed to leave his jail cell for temporary visits home. On one of these visits, he fled the country, but was caught in Spain, extradited to New York, and later died in prison.

Tweed's legacy of political organizing, influence peddling, and overall corruption remains unsurpassed.

Will Sellers is a graduate of Hillsdale College and an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of Alabama. He is best reached at jws@willsellers.com.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of 1819 News. To comment, please send an email with your name and contact information to Commentary@1819news.com.

Don’t miss out! Subscribe to our newsletter and get our top stories every weekday morning.