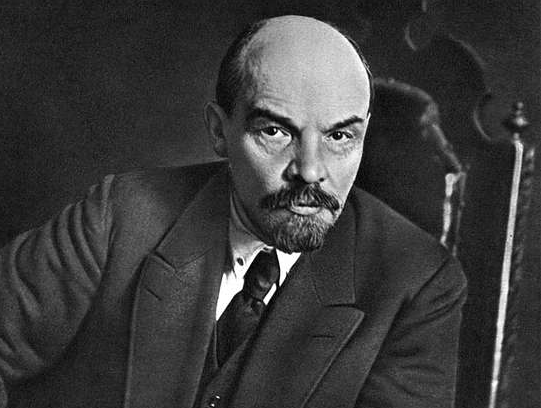

Vladimir Lenin died 100 years ago this month.

An unlikely revolutionary, Lenin’s story was not one of meager beginnings or social depravation. He came from a family of means that had little connection with the proletariat he came to champion. He was well educated, attended college, and became a lawyer.

During his “education,” he was radicalized when exposed to Marxism and embraced its view of 19th century revisionist history. Throwing facts aside, the history lessons he accepted were those of class struggle; of the haves vs. have-nots, of capitalism vs. socialism, ultimately concluding that the end of history was a workers’ paradise where everyone was equal and shared everything in common. Obtaining that result was now his goal.

Lenin’s evil genius was to take the tenets of Marxism and superimpose them on his Mother Russia. Unlike the more modern Western European countries, Russia had no real history of government organizations that balanced power and allowed for the popular participation of elections. Instead, Russian history saw government as the one strong man expressed in people like Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and other autocrats who were absolute dictators in the most totalitarian sense. The ideas of the enlightenment as it related to government, freedom of dissent, and liberty of conscience were seeds never germinated in Russian soil.

While Marx’s ideas in other parts of the world were discounted because they were incompatible with colloquial, cultural experiences, in Russia they had a chance of succeeding because its social structure was different. Primarily agrarian, with an economy barely touched by the industrial revolution and an Orthodox religion hardly sympathetic to the lower classes, Russia was ripe for revolution.

Though the pre-Bolshevik czars were not loved, they were at least tolerated and occasionally made attempts to liberalize Russia. Even with a pogrom here and there, the lower-class serfs had minimal creature comforts, the tax burden was bearable, and the government remote.

This would change with Russian entrance into World War I.

As Russia mobilized for war, patriotic fervor swept the country, unifying everyone in what was predicted to be a short and simple conflict. When the conflict was not quickly concluded, this nationalism receded, as support for the war drained the population of both food and money. When military successes remained distant and casualties mounted, the czar was ultimately forced to abdicate in favor of a coalition government of sorts.

Unfortunately for the czar, he had believed his senior military officials and their optimistic view of Russia’s military might. He hitched his entire reputation to supporting the war effort, and when stalemate caused the economy to tank, he took the easy way out and simply resigned.

Lenin now had his opportunity. He had looked for that perfect storm of confusion, instability, and conflict and now had it. Without a czar as a national center of gravity, Russia was ripe for a new leader, but Lenin wouldn’t have been anyone’s first choice. An exile in Switzerland, he was not popularly well known. As a writer of political tracts, his audience was limited to middle class Russian radicals, but his historical interpretation that war was a tool of imperialists and capitalists caught the eye of German intelligence.

In one of the most significant expressions of the law of unintended consequences, Germany provided transportation and support for Lenin to enter Russia. The thought was that Lenin would end the war, and rather than being divided militarily on two fronts, Germany could focus its energy on defeating the Western allies.

For Lenin, ending the war with Germany, although costly and consequential, would stanch Russia’s bleeding figuratively and literally. Plus, it would give him a platform to argue that his performance in bringing peace merited a mantle of leadership for other initiatives.

But Lenin was in the minority in what amounted to a coalition government, and even with his articulate speeches and engaging personality, his ideas for Russia’s future were not well received.

Minority status, though, has never prevented revolutionaries, much less communists, from succeeding. Status was status; minority or otherwise, it gave Lenin an aura of legitimacy allowing him a toehold that he would parlay into a foothold to gradually gain control of the government.

Using what limited power he had to obtain influence and consolidate his grip of authority, Lenin made his plan work. He understood that in revolutionary situations, masses matter most, and so he worked to gain acceptability with the lower classes as well as the military. At the end of the day, he had bypassed both the middle and officer classes with an appeal to serfs and enlisted men to support him.

He organized them into soviets, or local councils who would have governing authority much like our counties and states. Initially this authority was used to nationalize all industries and confiscate land to create collectives for everyone. Equality was guaranteed since the state owned everything, and the workers shared in the fruits of their collective labor.

But this didn’t work. Not at all. While farmers and factory workers had experience in doing their specific job, they had neither the education nor experience in governing or actually managing anything that the vast collectives required. Things fell apart in a hurry.

Disagreements were met with brutal suppression, and because Lenin had the army under control, summary executions for dissenters were easy. In a matter of no time, Lenin’s regime was no different than those of the czars. Even though different classes might be in control with different theories of government validating their actions, the net result for the country was the same: dictatorial control, brutal repression, and an unaccountable governing elite.

Lenin’s legacy was devastating for Russia, if not the world. He created an ideology that resulted in the deaths of tens of millions and repressed the very people he sought to liberate.

Will Sellers is a graduate of Hillsdale College and an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of Alabama. He is best reached at jws@willsellers.com.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of 1819 News. To comment, please send an email with your name and contact information to Commentary@1819news.com.

Don’t miss out! Subscribe to our newsletter and get our top stories every weekday morning.