MOBILE, Ala. (AP) — Shortly after Hurricane Sally wreaked havoc on Mobile’s Bienville Square in September 2020, an idea emerged: Use the fallen wood to make works of art. The healing notion was straightforward. The wood itself, it turned out, was as complex as its history.

Experienced wood-turner Fred Retting contributed a standout piece to a Mobile Arts Council exhibition of works made from fallen Bienville Square oaks. It’s accompanied by a note saying, “This was the most difficult wood I have ever worked with.

“This is going to sound a little farfetched, this is just my way of thinking, but I’m suspecting that under the duress of the wind and the rain, the stress and strain, the trees put a lot of energy into trying to stay upright,” Rettig said. “The wood was cracked all the way through. I would take a regular piece of wood that I would think was beautiful on the outside and I would start bringing it down to size, and there were cracks on the inside.”

Rettig went on to say that every artist that worked with this wood said it was very difficult. Lucy Gafford, executive director of the Mobile Arts Council, seconded that.

“That was the consensus from a lot of the artists, that the wood was really problematic,” she said. It held hidden cracks. It broke tools with its hardness and broke at least one trailer with its sheer weight. It was slow to dry and stabilize.

“There were a lot of obstacles with the wood itself being particularly difficult,” Gafford said. “We appreciate the artists who did manage to create works out of it because if it hadn’t been Bienville wood, no one would have made anything from it. … No one would have used it if it didn’t have that sentimental value behind it.”

Anyone interested in seeing the results has a few days left to do so. The Fallen Bienville Oak Exhibition has been on display this month at the Mobile Arts Council Gallery in the street front 1927 Room at the Mobile Saenger Theatre. It will be on display through March 31.

Artists who picked up sections of limbs and slabs of trunks in January 2021, under the supervision of Urban Forester Peter Toler, had a little over a year to transform the raw material. The results take a wide range of forms. Some made functional objects: A Tensaw Charcuterie Board from Delta Scott Woodworks, an electric guitar from Chris Fayland and “Sally,” an invitingly elegant chair, from Ben Reynolds and Azalea Home Custom Furniture.

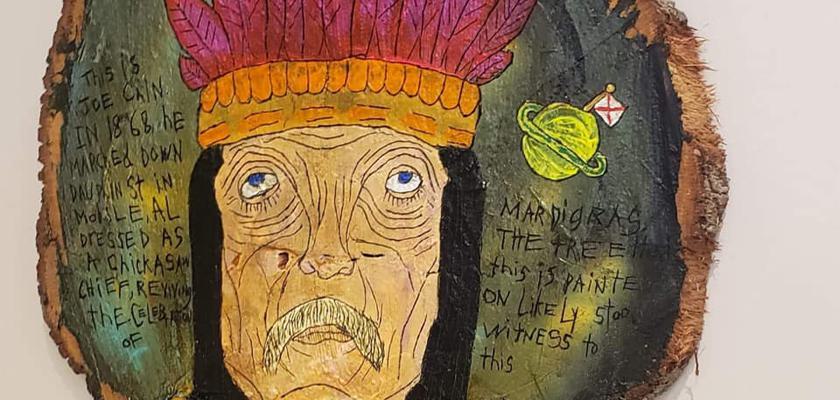

Other artists used the wood as a canvas for a variety of techniques, from carving (Gary Mason’s “Flowers,” to mixed media (Samantha Savage’s “Steampunk Ship”) to a variation on Kintsugi, the Japanese technique of mending broken pottery to turn flaws into features (Amanda Youngblood’s “Kintsugi Sisters”). Some commemorated the square or paid tribute to famous Mobilians, as in Abe Partridge’s tar-and-acrylic Joe Cain and Kathleen Kirk Stoves’ pyrographic portrait of Eugene Walter. The latter, titled “Hurricane Party,” bears the Walter adage: “When all else fails, throw a party.”

“I was impressed with the variety of works that people created and the different techniques that were used,” said Gafford. “I never expected a fully finished guitar out of that wood. Especially getting all the feedback about it being so terrible to work with.”

She was also shocked, she said, that some of the artists donated the proceeds from any sale of their works to Mobile Arts Council. “There was no expectation of anybody doing that,” she said. (Some of the works are not for sale. Others are, with prices ranging from under $200 to over $2,000.)

As for Retting, he can look at his vase with relief. He said he put about 50 hours of work into the project, a vase with an elaborate topper inspired by Bienville Square’s fountain.

“It was intense, trying to get this piece complete,” he said. “There was only one piece that I did not have to repair during the process.”

For the vase, he started with a piece of wood that weighed 40 pounds. Roughing it into shape got it down to 26 pounds. Hollowing it out took it down to five and a half pounds. That took drastic measures because he knew he had to get out as much of the still-green interior wood as possible so that the remainder could dry and stabilize. “So it wouldn’t crack in two while it was sitting on the stand,” he said.

He has a photo of an intermediate stage where the project was held together by something you don’t normally find in a woodworker’s shop.

“After I got the piece cut, I knew if I didn’t do something to hold it together I was going to be in trouble,” he said. “So I went and bought some radiator hose clamps, and there’s six sets of hose clamps on this piece holding it together.”

Like other artists, he had to find a way to use the cracks he couldn’t eliminate. He filled them with turquoise “representing water flowing from the fountain.”

“At the end I had fun,” he said. He was still polishing the piece the day he delivered it. “I got through an hour before the deadline,” he said.

“If those trees could talk, those trees were planted in 1890, from what I’ve read,” he said.

“If” they could speak? Thanks to Rettig and the other participating artists, now they do.