“How you doin’?” the security guard said as I walked inside the public library.

“I’m getting my library card today,” I told him.

“Congratulations,” he said.

I stepped through the front doors into the surgically chilled air of the Birmingham Public Library, one of the largest library systems in the southeastern United States. I’m new in town, a library card was my first order of business.

No sooner had I entered than I could smell books. Lots of books.

The scent of books is a powerful hallucinogenic. When you see this many books in one place, your imagination runs away with you. You are among the greatest minds of humankind in paperbound form.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a better book collection than the one the Jefferson County Library Cooperative system has. The system consists of 39 branches, with an annual checkout rate of over 3.7 million books.

When I reached the front desk, ahead of me was a young man in line. He was maybe 15. He had shaggy hair, holes in his shoes, ratty clothes, and shy mannerisms which seemed to scream “low confidence.”

I know the look of the underprivileged. I was one.

He was checking out a large stack of books. I glanced at his literary selections: McMurtry, Coben, Connelly, a biography of Theodore Roosevelt, Tolkien. Not a bad mix.

He placed his books on the counter. The librarian was an older Black woman wearing pearls. She asked how he was doing. He spoke with a pronounced stammer.

The woman scanned his books, she God-blessed him, and he left. I saw him rush outside and crawl into a car driven by a young mother. Before their vehicle exited the parking lot, he was nose-deep in Harlan Coben.

A hundred years earlier, that kid could have been me.

When I made it to the front desk, the librarian smiled. “Help you?”

“I’d like to get my library card, ma’am,” I said.

“Well,” she said, “Let me be the first to welcome you to the Birmingham Public Library.”

“Proud to be here,” I said.

And we got down to business.

My love affair with public libraries dates back to my first experience getting a library card when I was five years old. My mother rushed me into a public library because I had to pee, and the library had the cleanest public restrooms.

While we were inside, I got my library card. I was supposed to sign the card, except I didn’t know how to write my name at that age. So I drew a picture of a horse instead. Although, my drawing looked more like a depiction of Jabba the Hutt with extra legs.

That little paper card turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to me.

Because after my father died, I dropped out of school in the seventh grade. My education became a shipwreck. I was a lost boy.

Still, no matter how bad things got, I never quit using the library.

Librarians took a special interest in me. Each week, a guild of elderly women in reading glasses curated stacks of books just for me. They fed me a steady diet of Westerns, romances, thrillers, historical fiction, crime novels, biographies, travelogs, classics, National Geographics. They introduced me to Samuel Clemens.

There are no two ways about it, I am a writer thanks to the American library collective. I am the love child of librarians and a county system that is funded by public taxation.

My literary beginnings originate with a humble brigade of white-haired women who knew the intricacies of the Dewey Decimal System. They refused to watch me disappear into the outer darkness. I owe my education to them. I owe them my career.

A few years ago, I gave a speech before a room full of 800 librarians from around the country. My speech was supposed to be lighthearted and entertaining, but when I gazed at the roomful of men and women who daily dedicate their lives to supplying young people with the printed word, I started to cry onstage.

I thanked them all sincerely for what they had given to me personally. When I finished, a mass of little white-haired women in tennis shoes and Majorica pearls swarmed me in a big group hug. These librarians hailed from New Jersey, Minnesota, West Virginia, Florida, Mexico, Mississippi, Arkansas, Kansas, and California.

Their eyes were just as wet as mine. They were old enough to be my grandmothers.

They doted on me. They told me I was talented. They asked me to sign their books. One lady had me sign her baseball cap. Another woman asked if I would sign her T-shirt with a Sharpie, which was weird. But sweet.

That same night I realized something about myself. I learned that no matter how old I get, I will always be that aimless kid who feels confused about who he is. I will always be the boy who doubts himself. I will never outgrow these feelings. And I wouldn’t want to, either.

But somehow, every time I visit a public library my entire life seems to make a little more sense.

Which is why the most precious thing in my wallet is my library card.

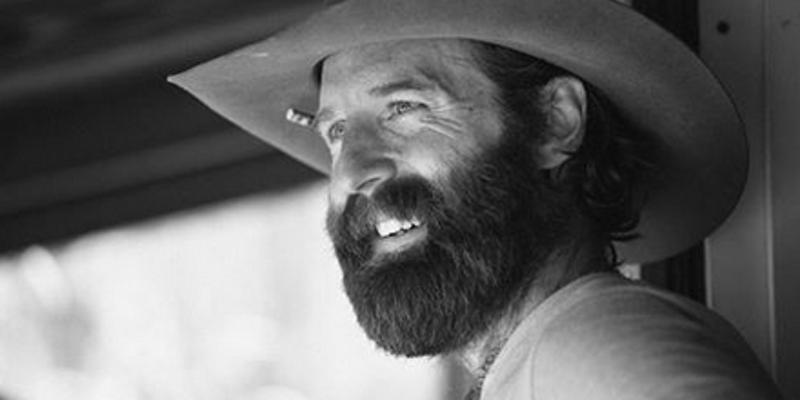

Sean Dietrich is a columnist and novelist known for his commentary on life in the American South. He has authored nine books and is the creator of the “Sean of the South” blog and podcast. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of 1819 News. To comment, please send an email with your name and contact information to Commentary@1819News.com.