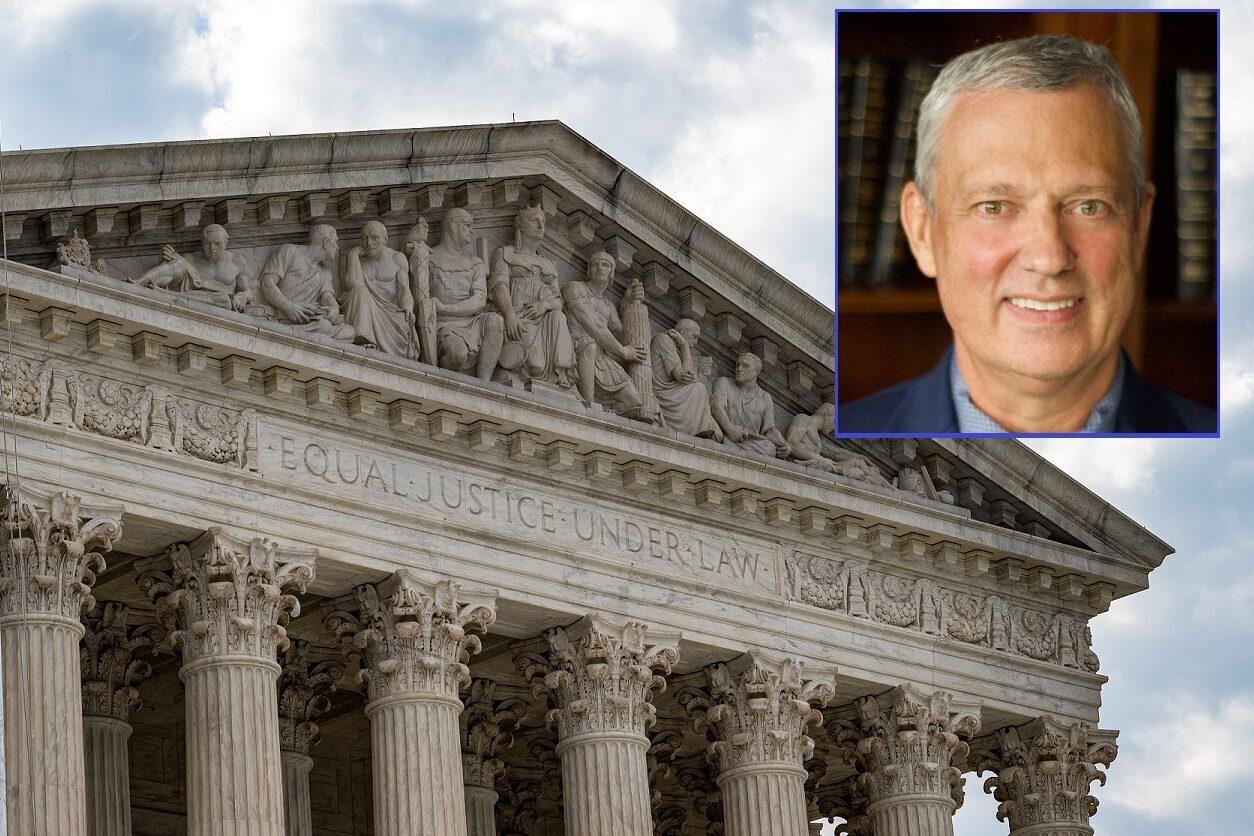

The recent resignation of Ethics Commissioner Stan McDonald has raised questions about the potential constitutional frailty of the ethics law that compelled him to resign after admitting to donating to political candidates.

McDonald resigned on Wednesday, one week after going toe-to-toe with State Rep. Matt Simpson (R-Daphne) over a proposed bill to overhaul Alabama's ethics laws.

See: House passes ethics law overhaul — 'These are the lines; if you cross them, we're coming for you'

During an appearance on FM Talk 106.5's "Midday Mobile," Simpson claimed McDonald admitted to a felony earlier that day by violating existing ethics law prohibiting Ethics Commissioners from participating in "partisan political activity" and making political contributions.

McDonald resigned the same day he published a public apology to Simpson, in which he admitted that his potential violation of the law was the reason for his departure.

Section 36-25-3 (e) of the Alabama Ethics Act states the following:

"All members, officers, agents, attorneys, and employees of the commission shall be subject to this chapter. The director, members of the commission, and all employees of the commission may not engage in partisan political activity, including the making of campaign contributions, on the state, county, and local levels. The prohibition shall in no way act to limit or restrict such persons' ability to vote in any election."

The punishment for violation is a Class B felony.

If pursued, would the felony charge have passed constitutional muster?

The confusion and ambiguity of Alabama's ethics laws, which began the whole debacle, is displayed in the prohibition against commission members donating to political campaigns. By all accounts, the legality of the state's ban has never been decided in court, and legal experts admit the courts could go either way.

Federal Election Commission (FEC) guidelines list entities that cannot contribute to a campaign: corporations, labor organizations, federal government contractors, foreign nationals, and those making donations in the name of another.

Additionally, the Hatch Act of 1939 restricts the political activity of individuals principally employed by state, District of Columbia, or local executive agencies who work in connection with programs financed in whole or partly by federal loans or grants. However, the Hatch Act does not address campaign contributions. Instead, it restricts certain state workers from running for partisan political office, using their position to influence an election and coercing or advising employees to contribute to an election.

The Act reads, "Only those employees of the agency who, as a normal and foreseeable incident of their employment, perform duties in connection with activities financed in whole or in part by the federal grants or loans are subject to the Act."

In 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United V. FEC that prohibitions on electioneering communications and independent expenditures by corporations were unconstitutional. However, it did not affect the ban on corporate contributions.

Laura Clark, a constitutional attorney and president of the Alabama Center for Law and Liberty, said the ban's constitutionality is ambiguous and open to dual interpretations.

"Whether the statute prohibiting members of the Ethics Commission from contributing to campaigns is a violation of free speech is ambiguous," Clark said. "In Citizens United v. FEC, the Supreme Court ruled the First Amendment prohibits the government from preventing corporations from donating to political campaigns. Under Supreme Court jurisprudence, corporations are people and free speech rights extend to them. However, in this case, the law is prohibiting a person working for the government. Theoretically, the government should not be able to prohibit what he does as a private citizen. But he is also a civil servant and should not be partisan."

Former U.S. Rep. Mo Brooks (R-Huntsville), a retired attorney, echoed Clark in pointing out the ambiguity of the ban.

"If I were [McDonald's] attorney, my argument in court would be that it is unconstitutional to bar a citizen from participating in free speech activity," Brooks told 1819 News. "And the federal courts, time and time again, have ruled that campaign contributions are a subset of freedom of speech because they magnify your voice."

"This specific kind of statute, if challenged, would be a case of first impression, as far as I know. But you've seen how the United States Supreme Court has ruled on contribution restrictions in cases like Citizens United. So, there are limits on a government's ability to stop citizens from participating in election activities via such things as contributions. Now, whether this particular statute would fall inside or outside that prohibition, you don't know until you contest it in court," he continued.

McDonald was not terminated. Instead, he resigned, meaning that litigation challenging the ban would be unlikely in this case.

"I promise you, on this one, there are two sides to the coin," Brooks concluded. "I would be able to argue either side, as I am sure that any lawyer worth his salt would be able to do, and then the courts have to decide."

To connect with the author of this story or to comment, email craig.monger@1819news.com.

Don't miss out! Subscribe to our newsletter and get our top stories every weekday morning.