Dear Naomi Judd,

I heard you died yesterday. You were 76 years young and lovely. Your family said you died from “mental illness.” No sources close to your people have officially said it was suicide, but it doesn’t take a nuclear engineer to guess what happened.

I saw the headline in the paper, and it ripped me apart. Any hint at the word “suicide” always does this to me. I am haunted by that word.

Growing up, that word followed me like a swarm of locusts. It was like a heavy cloud over me. You know the character Pig Pen, from the “Peanuts” comic strip? You know how a cloud of dust is always following him around wherever he goes? That was me and the stigma of suicide.

My father died by suicide, just like you. Or, rather, he died of “mental illness,” like your family told the reporters. Which is a more accurate way of saying it, when you think about it. Nobody ever dies of suicide. It’s the mental illness that kills a person before the suicide ever does. It’s the untreated abscess in the human psyche that festers and kills a person. Not the gun.

Earlier this year, I was in Tybee Island for a book event. At our hotel, I happened to meet a guy who was in a wheelchair at the front desk. We made friends. There was something about him I liked. Something different. Something special. He came to my show that night. He sat in the back row while I told stories about my childhood to a small theater of snoring people. He laughed at my jokes. He bought a book.

His name was Lynn. Before the wheelchair, he was a touring rock-and-roll musician. He traveled with bands, played lead guitar, and had a good time. And you could tell he was a good guy.

It turned out that Lynn and I had a few things in common. During his boyhood, his father died of suicide just like mine did. And when Lynn was middle-aged, his mentally ill brother shot him in the spinal cord, then shot their mother, then took his own life. They found Lynn lying on the floor, half paralyzed.

I asked how Lynn had survived the most horrific turn of events I’d ever heard recounted by a human being. And he said something I will never forget. Something so cliché and overused I couldn’t believe he said it.

He said, “Man, all we can do is love each other through it.”

Lynn and I had a pretty good week together on Tybee Island, hanging out at the hotel, kicking around on the beach. The World Series was on TV. We sat among the tiki bars with twinkling lights and listened to some genuinely crummy live music while the Braves decimated the Dodgers. We laughed a lot. He was an instant friend.

After we both went home, we kept in touch. We talked on the phone a lot. We texted each day. He wrote to me after every mediocre column I produced and encouraged me.

Then came the week he quit calling.

I knew something was off. I kept texting, kept emailing, kept calling, kept asking if he was okay. No response.

One day, I called his phone and a strange male voice answered. It was Lynn’s brother. “Lynn passed away,” the man told me.

I felt a cold shock run through me.

“How did it happen?” I said. I was thinking it was a heart attack. Or maybe a serious infection. Perhaps an accident. But it was no accident.

His brother said that Lynn had rented a hotel room on the beach. Late one night, when Lynn got his courage up, he wheeled himself onto the sand and took his own life with a pistol.

I dropped the phone and started sobbing. Deep, guttural sobs. I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t think.

The shock brought a lot back for me. A lot of things I wish I could forget. Suddenly, I was a child again, standing in the sheriff’s office and a deputy was telling my mother that my old man used his big toe to pull the trigger on a hunting rifle. I was remembering how badly it hurt when people shook our hands at the funeral and how they didn’t know exactly what to say. I remembered how the world seemed so cold. I remember how alone I felt. Sometimes I remember too much.

I’ve never met your daughters, Naomi. I’ve never met anyone famous except Patty Duke one time. But I know that your daughters, lovely women who lost their beautiful mother to mental illness, now belong to a club of which I am also a member.

And I believe all we can do is love each other through it.

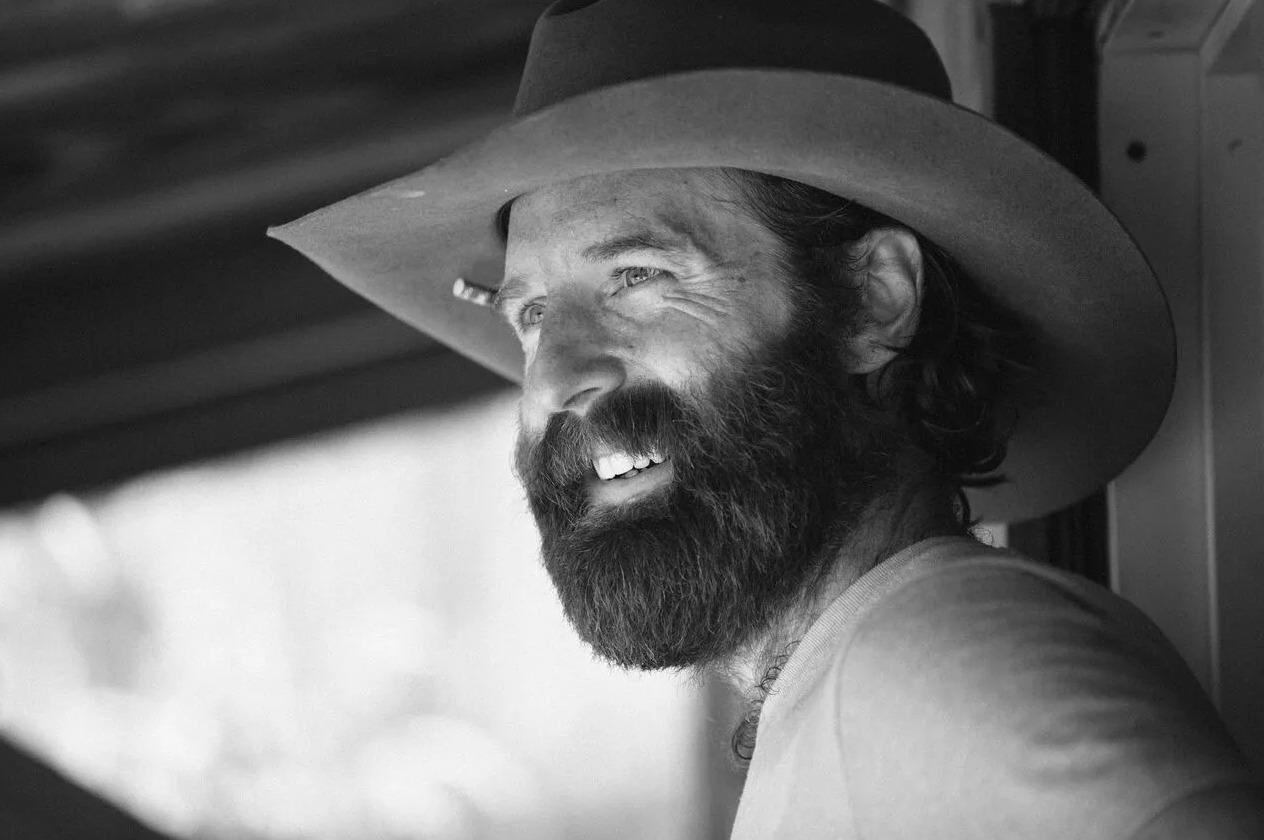

Sean Dietrich is a columnist and novelist known for his commentary on life in the American South. He has authored nine books and is the creator of the “Sean of the South” blog and podcast. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of 1819 News. To comment, please send an email with your name and contact information to Commentary@1819News.com.

Don’t miss out! Subscribe to our newsletter and get our top stories every weekday morning.